In their pursuit of working in Japan, three passionate Kenyan learners—Baraka, Luwate, and Aoko—shared the stories behind their Japanese language journey. Each path was unique, yet all were marked by curiosity, challenge, and growth.

Baraka’s interest in Japanese began with anime. His initial goal was simple: to enjoy his favorite shows without relying on subtitles. For Luwate, the journey started during the COVID-19 pandemic. He didn’t have a clear reason at first, but once he began, the language quickly became an obsession. Aoko’s spark came during her internship in Japan, where she wanted to communicate more naturally with her roommates and friends. She found herself drawn in by the musicality of Japanese—the pronunciation and intonation felt captivating.

Their commitment deepened through pivotal moments. Baraka’s turning point came during his first conversation with a Japanese speaker on the italki app. That exchange opened his eyes to the beauty of cross-cultural connection. Luwate experienced two major shifts: one was a HelloTalk conversation that led to lasting friendships, and the other was a bold decision to register for the JLPT N2 exam while still at N3 level. The pressure pushed him to study intensely, and he passed on his first attempt. Aoko committed seriously in 2022 when she enrolled in a Japanese language school in Tokyo, determined to pass formal exams and improve her fluency.

Each learner had a different approach to study. Baraka started as a self-learner and reached an N4 speaking level before taking Japanese as a minor at USIU University. With guidance from Nakamura-sensei, his confidence and fluency grew. Luwate also self-studied up to N4 before joining an elective course at Strathmore University. Though he found himself ahead of the curriculum, he appreciated the structure and reinforcement. Aoko began by teaching herself the basics, then joined Rikkyo University’s Japanese language program in Tokyo to deepen her skills.

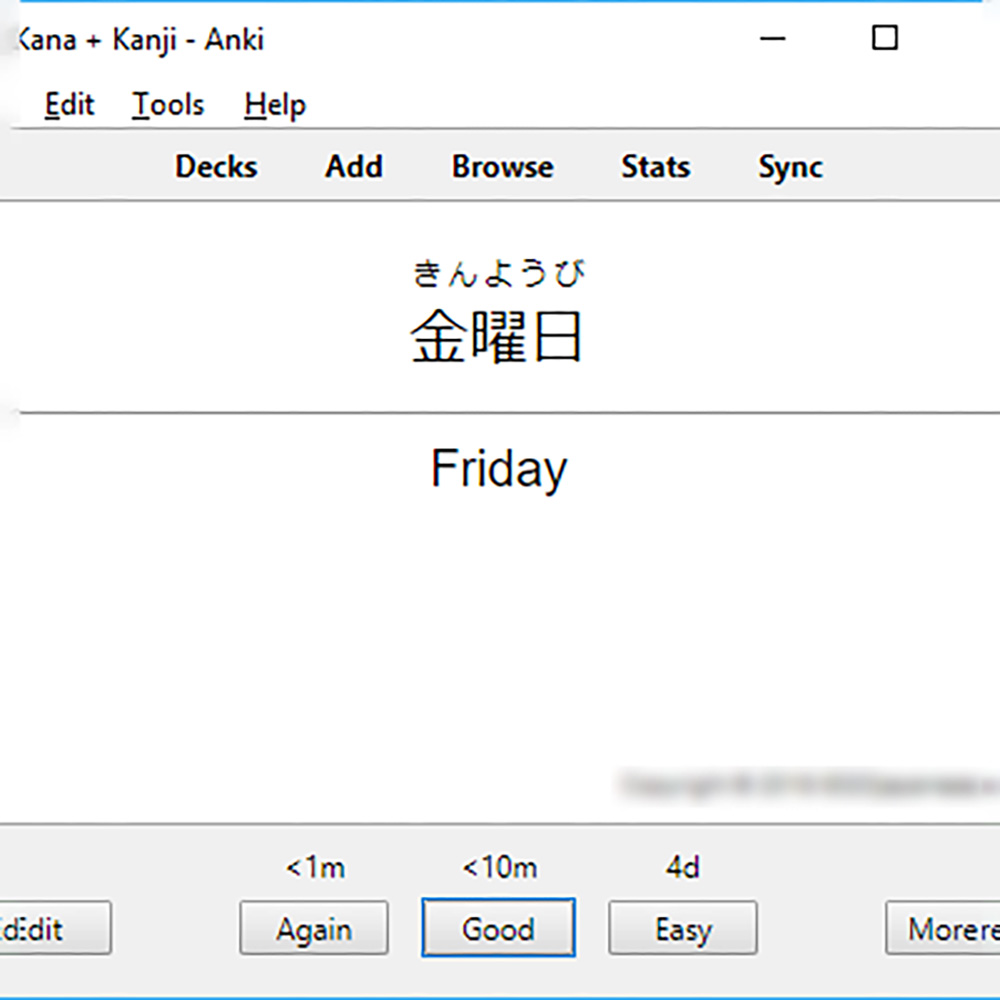

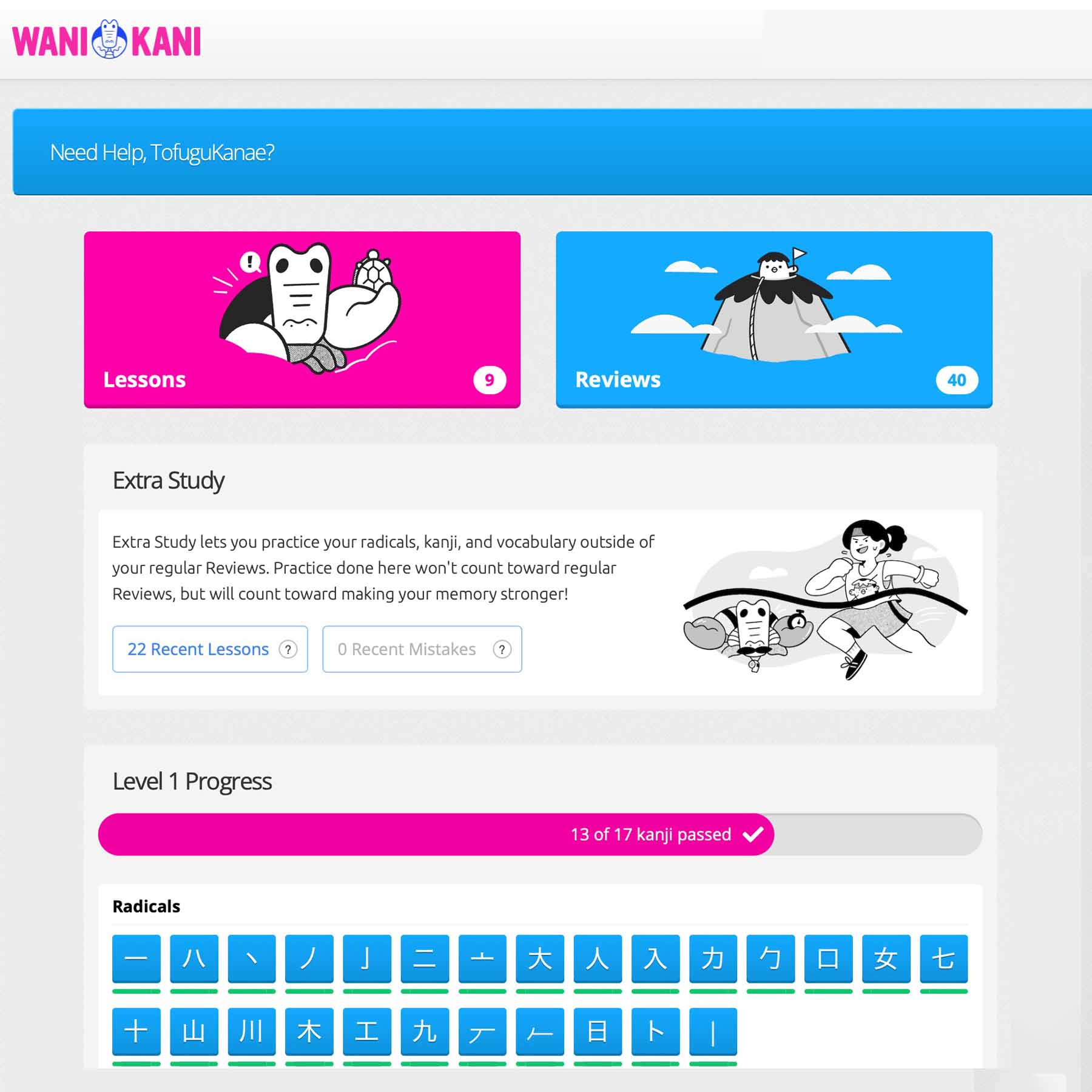

Their methods varied, but all emphasized the importance of immersion and repetition. Baraka relied heavily on audiovisual tools to refine his pronunciation. Luwate experimented with many techniques before settling on what worked best for him—apps like WaniKani for kanji and watching Japanese movies without subtitles to train his ear. Aoko immersed herself in Japanese content on Instagram and YouTube and practiced daily through conversations at her part-time job in Tokyo. They all agreed that incremental learning—absorbing knowledge through repeated exposure and experience—was key to their progress.

In terms of resources, Baraka highlighted Todai and HelloTalk, especially for JLPT preparation. Luwate leaned on Genki and Tobira textbooks, WaniKani for kanji, and Anki for vocabulary. Aoko relied mainly on Rikkyo University’s materials, Genki N5 resources, and YouTube tutorials.

Interaction with native speakers played a major role in their development. Baraka didn’t travel to Japan but made Japanese friends through HelloTalk. Luwate connected with native speakers via HelloTalk and LINE, including an English PhD student who helped him practice. He also visited Japan for ten days after the pandemic, engaging in spontaneous conversations—one of which ended with a stranger buying him dinner and covering his train fare. Aoko, already studying in Japan, practiced regularly through her part-time job and daily interactions.

Cultural experiences shaped their learning in profound ways. Luwate emphasized the importance of understanding concepts like honne and tatemae and knowing when to “read the air” (kuuki o yomu). He believes cultural fluency is essential to expressing personality without miscommunication. Baraka, whose personality leans toward humor, had to learn how to integrate that into Japanese culture without being misunderstood. Anime helped him grasp different speech levels like keigo and sonkeigo and gave him insight into everyday life in Japan. Aoko found that visiting traditional inns (ryokan) and navigating daily life—like shopping—deepened her understanding. Early challenges, such as misreading labels and buying the wrong items, motivated her to improve her Japanese further.

Miscommunication, they agreed, is part of the journey—and often the most memorable part. Baraka recalled a moment at work when he tried to express a desire to be “deep” (fukai) in conversation with a visiting researcher. Unfortunately, the word came across as overly intense or even inappropriate, leading to an awkward exchange that he now laughs about. Luwate shared several humorous slip-ups. One involved telling a Japanese friend that he “plays with high school friends” (高校生の友達と遊んでる)—which sounded like he was hanging out with current high schoolers—instead of saying he spends time with friends from his own high school days (高校生時代の友達と遊んでる). Another moment came during a shopping trip to Maasai Market with a Japanese companion, where he used the word pantsu (パンツ)—which in Japanese mainly refers to underwear—instead of zubon (ズボン), the correct term for trousers. The confusion sparked laughter and became a lasting memory. Aoko described a moment at her restaurant job when the manager asked, “Daijoubu desu ka?”—intended to check whether she had finished washing the dishes properly. She responded with a cheerful “Hai!” thinking she was asking about her wellbeing. It was a small misunderstanding, but one that highlighted the nuances of context in Japanese communication.

When asked how long it took to feel comfortable communicating in casual or business contexts, Baraka estimated about a year. Luwate found casual conversations came more quickly—within five to six months, thanks to HelloTalk—but speaking confidently with unfamiliar Japanese speakers took closer to a year. Business Japanese remains a challenge, as the vocabulary and tone differ significantly from casual speech. Still, he believes immersion is key: “You understand a language better when you’re in the environment.” Aoko felt comfortable in casual contexts after about three months, but she’s still working toward fluency in business settings, balancing study with work and daily life.

Looking back, their advice to new learners was unified and heartfelt: don’t stop. Keep pushing. Practice a lot. They encouraged learners to make the process enjoyable—by connecting language learning with hobbies, culture, and personal interests. They advised against overcomplicating things or feeling pressured to take the JLPT unless it aligns with one’s goals. “Plug it into the ecosystem if you want to—but don’t force it.”

If they could start over, Baraka said he would focus more on reading and aim for a balanced learning structure. Luwate wouldn’t change much, but he would place greater emphasis on speaking. Aoko wished she had taken her studies more seriously from the start, making more time and effort to learn.

Collectively, they offered powerful reflections; be comfortable making mistakes—fail forward. Don’t place heavy expectations on yourself; focus on learning in the present. Stay humble. Don’t let praise or recognition distract you from your goals. Make sure your language level holds up even on your worst days. Treat yourself like both a computer and a child—absorb everything. They also emphasized that language is more than words—it’s a container of worldview. Understanding how you learn best and adapting your methods is key.

Baraka and Luwate, who met at a Japanese speech contest in 2020, still recall their first impressions of each other’s fluency. Upon hearing one another speak for the first time, they both thought: “This guy is insane.”